Reevaluating the revolution that fed the world

The Green Revolution transformed global agriculture. Are its critics right?

The fear of Malthusian catastrophe dominated the late 20th century – the idea that exponential population growth would soon outstrip food production, leading to inevitable famine and starvation. In The Population Bomb, published in 1968, the Stanford biologist Paul Ehrlich warned that “in the 1970s hundreds of millions of people will starve to death in spite of any crash programs embarked upon now. At this late date nothing can prevent a substantial increase in the world death rate." The world braced itself for the catastrophe of a human society reaching its natural limits.

But that didn’t happen. Funded by Western philanthropists and international organizations, scientists created new high-yielding varieties of rice, wheat, and corn, as well as new pesticides, herbicides, and fertilizers, in a concerted research effort known as the Green Revolution. These new varieties and techniques dramatically increased food production across the developing world and ensured that no Malthusian famines ever occurred. The figurehead of the Green Revolution, an Iowa plant breeder named Norman Borlaug, would go on to receive the Nobel Peace Prize and be credited with “saving more lives than any man in history.” It was a Promethean story – humans using our ingenuity to defy the limits that nature put on us.

But its legacy has been tarnished by critics who argue that input-intensive farming has destroyed land and water reserves, making people poorer and sicker. Now the rallying call among activists is for food sovereignty – the right to “healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods” – the term being a pointed reference to the Western funding behind the GR. In the face of this criticism, the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (a Gates-/Rockefeller-funded organization trying to promote the same model in Africa) dropped the “Green Revolution” from its name in 2022, now known simply as AGRA. It’s now a faux-pas in agricultural policy to advocate for another Green Revolution.

For a long time, I dismissed these criticisms without much thought. But that was because the Green Revolution is central to my personal narrative. Growing up in India – one of the epicenters of the GR – I learnt about it as one of the landmark events in India’s history. My parents could have grown up malnourished if not for the food abundance created by the GR. It gave me a visceral sense that science can literally save the world, a belief that has influenced my research path.

But it’s important to revisit the Green Revolution with clear eyes, both for me and for the world. Climate change threatens agriculture and food security today, and the GR remains the only historical example of rapidly scaling food production to match population growth – making it either an essential blueprint for future food security, or a cautionary tale about unsustainable intensification. And for me, the reassessment is personal; I need to know whether my belief in human ingenuity is actually built on shaky foundations. So let’s figure out the Green Revolution’s actual legacy.

Disclaimer: I am not an expert on the Green Revolution. I am just an economist who generally knows how to read papers. I was aware of some of these papers before I started this review, and not others. I come into this review as an outsider. This disclaimer matters because there are people who have spent literal decades studying the question I’m trying to answer. I’m not declaring that I know better – I just needed to find an answer for my own satisfaction.

Did the Green Revolution feed the world?

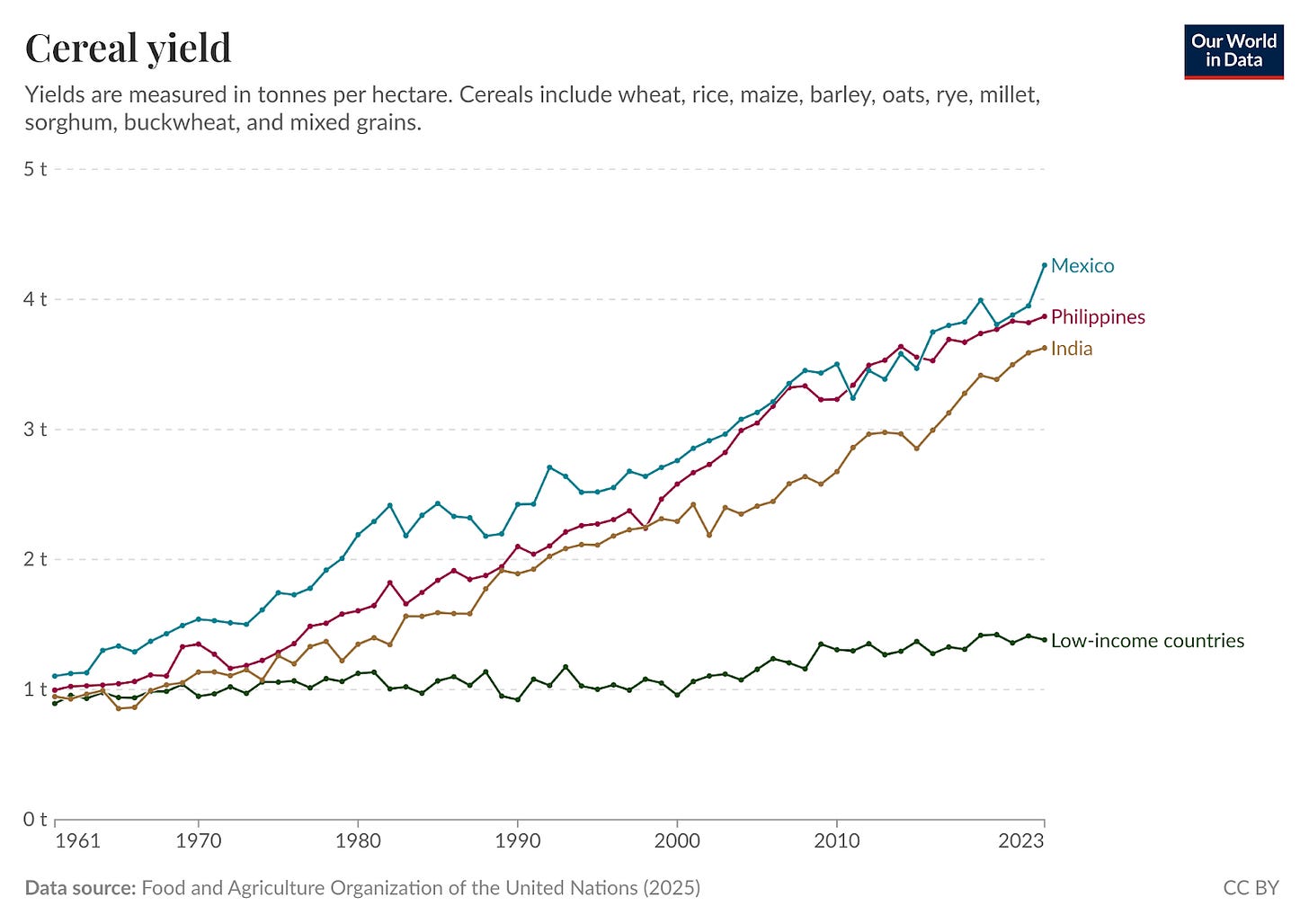

Let's start with the most basic question: did the Green Revolution increase agricultural productivity in the developing world? Yes. The simplest version of this argument is that cereal yields in the countries that were the epicenter of the GR increased dramatically, especially compared to yields in low-income countries.

In fairness, the fact that yields grew does not mean that the GR – and its particular package of high-yielding seeds and input-intensive farming – was responsible for those yield increases. Maybe the GR simply coincided with other policies that led to more productive agricultural sectors in countries, or maybe there was just a natural upward trend in yields. Is there any evidence that the GR caused that yield growth?

There is, in the form of a quasi-experimental study by Gollin et al (2021). They note that high-yielding seed varieties for different crops were released at different times. They use this as their natural experiment, comparing yield growth in crops that saw high-yielding seed varietals (HYVs) developed earlier, against crops that saw HYVs developed later. Assuming that these crops would have seen parallel trends in yields without the GR, this comparison tells us the true effect of the GR on crop yields. Gollin et al find that, on average across crops, HYVs increase yields by 9% within 10 years of their introduction, with effects climbing to 75% over 40 years. They argue that this gradual effect makes sense, both because adoption of HYVs is gradual, and because once there is a breakthrough, HYVs are improved upon by successive generations.

In short, we don’t have to be concerned about whether the basic concept of the Green Revolution is fictitious. At a bare minimum, it did increase food yields across the developing world.

Did the Green Revolution make people richer?

So we’ve established a baseline fact that the Green Revolution did increase food yields. The next step is to ask, did that yield growth make people and countries richer? Unfortunately, here is where the consensus ends.

Gollin et al argue that it did. They measure how “exposed” each country was to the Green Revolution at any point in time, based on the share of land that was planted with each crop, and whether that crop had an HYV seed released at that point. Intuitively, countries that grow more rice and wheat (where HYVs were released in 1963 and 1965) would see an earlier boost from the GR than countries that grow more sorghum and cassava (where HYVs were released in 1983 and 1984). So comparing countries exposed earlier to those exposed later allows us to measure the impact of the GR.

Thirty years after the start of the Green Revolution, more-exposed countries had a staggering 70% higher growth in GDP per capita than less-exposed countries. The authors argue that this is because the GR not only increased agricultural output (which directly increases incomes), but it also pushed people out of agriculture and into manufacturing/services employment (which indirectly increases incomes, since those sectors are more productive and thus pay better than being a farmer). Aggregating across countries, the authors calculate without the GR, the cumulative loss to global GDP would be $83 trillion! Taking this result at face value would suggest that the GR was one of the most important causes of development in the 20th century.

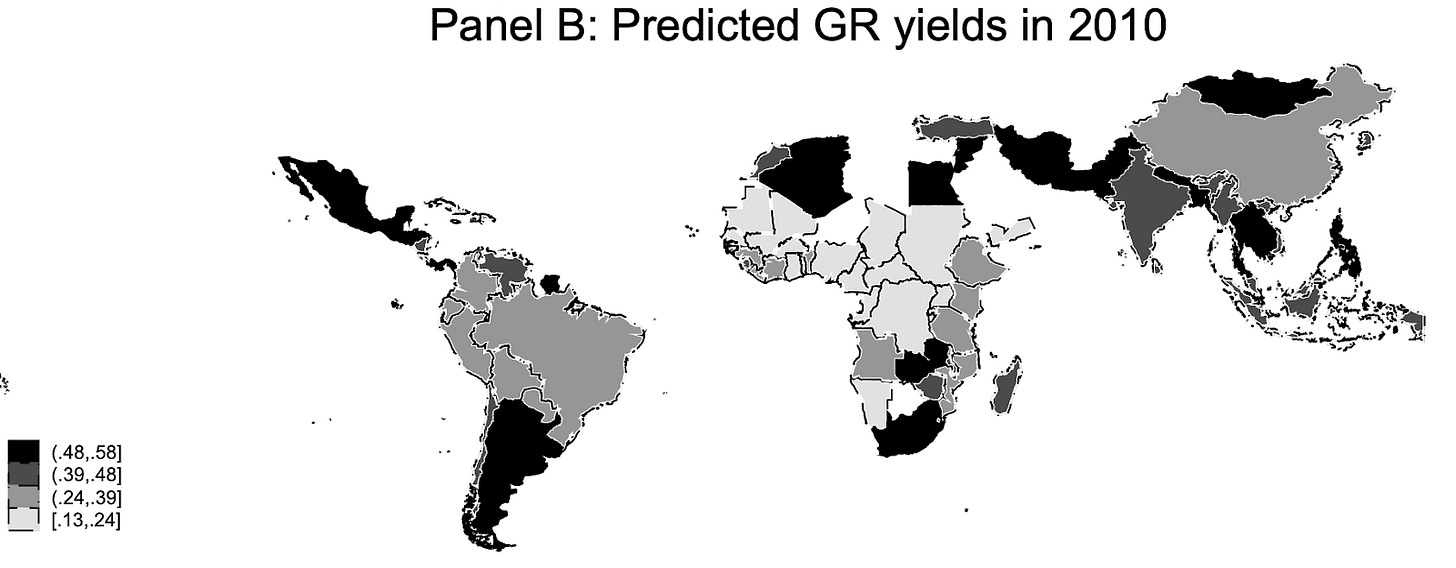

However, their measure of exposure reveals a thorny problem with their estimates. To see the issue, look at how the authors’ exposure measure is distributed across countries (note that the map is incomplete because they leave rich countries out of it):

The exact numbers are not important, but it jumps out that most of Africa has the lowest exposure – because HYVs for many important staple crops in Africa (sorghum, millets, cassava, etc) were developed decades later than HYVs for rice, wheat and maize. So when we compare income growth in “more exposed countries” to that in “less exposed countries”, we are implicitly comparing income growth in Asia/Latin America to income growth in Africa… and attributing those differences to the Green Revolution.

That seems bad! While exposure to the GR was certainly an important difference between Africa and the rest of the world, it wasn’t the only one. Attributing all the differences in income growth to the Green Revolution – not to colonial institutions, or to geography, or to any of the hundred and one theories for why Africa is poor – is just wrong. So the landmark study on the Green Revolution is uninformative about whether it accelerated economic growth in the beneficiary countries. Back to the drawing board.

How could incomes not increase?

You might say that I’m nitpicking over the study’s particular design issues – because if we accept that the Green Revolution increased yields, then it mechanically must increase incomes. If the additional produce is there, then someone has to be profiting from it, right? Wouldn’t that mean incomes are going up on average?

But there is an important subtlety that can lead agricultural productivity growth to be neutral or even negative for incomes. The question is about whether the higher yields pull people into agriculture, when those people would have otherwise moved into more productive jobs in the manufacturing or service sectors. If the Green Revolution caused more people to become farmers instead of moving to the city and finding higher-paying jobs, then it may have been neutral or even negative for incomes on average.

This is an important consequence of globalization, that wouldn’t occur in a country closed off to trade. After all, once you produce enough to feed everyone in a country, there’s no demand for more food, so there is no point in having additional people working in agriculture – so agricultural productivity growth would push people out of agriculture, with no tradeoff. However, when countries can export food, there is no “enough to feed everyone.” There are always customers for the food you produce, somewhere in the world. So making countries more productive at agriculture can make them specialize in exporting food to the rest of the world – which is bad for their growth in the long run, because specializing in agriculture means that a country has fewer people living in dynamic cities, fewer people working in the manufacturing and service industries that can serve as engines of growth.

This is exactly what Moscona (2019) argues happened during the Green Revolution. Like Gollin et al, he estimates how the agricultural productivity growth from the Green Revolution affected country incomes. But he uses a different natural experiment than Gollin et al. Rather than comparing countries with more vs less area planted in rice/wheat/maize, he uses the biophysical potential yield improvements from HYVs as his measure of exposure to the Green Revolution. Countries differ in their agronomic conditions due to their different geographies; some countries have environmental conditions that benefit more from HYVs than others, leading to differences in the impact of HYVs across countries. By comparing the income growth of countries with higher potential yield improvements from HYVs to that of countries with lower potential yield improvements, Moscona can estimate the impact of the GR.

Moscona estimates that the Green Revolution did not have any effect on national incomes on average. Actually, he shows that when you focus on the countries that were the most globalized, the Green Revolution had a negative effect on income – by increasing the agricultural labor force and reducing the speed of urbanization, just as in the story outlined above. This is why Moscona concludes that the Green Revolution did not increase incomes on average.

But Moscona’s methodology is also flawed, because of its focus on countries with the most potential yield improvements from HYVs. It’s not at all clear that these are the countries that actually saw the most yield improvements from the Green Revolution. Moscona doesn’t list the countries which have the highest value of this measure, but some of his tests suggest that his measure only weakly tracks actual benefits from the GR.1 So it’s really hard to take his results as evidence for anything about the GR.

The alternative approach: connecting yields to incomes directly

Both of the major papers studying the Green Revolution itself have deep flaws. What do we do with this? Instead of restricting ourselves to papers that study the Green Revolution specifically, we can learn more by looking at papers that study the relationship between agricultural yield increases and income growth more generally. The most helpful study in this vein is McArthur and McCord (2017), who estimate how agricultural yield increases affect incomes within a country. They use the fact that different countries have different access to fertilizer, based on how far they are from the factories where fertilizer is produced and exported to the world. So countries with more access to fertilizer have higher yields – and they use this access to fertilizer as a natural experiment for whether higher yields do in fact translate into higher incomes. If these regional differences really are only about access to fertilizer (and not, for example, being generally more central and connected), then their income differences are actually explained by the higher yields induced by more fertilizer access. They estimate that increasing cereal yields by half a ton/hectare increases GDP per capita by 15%.

How do we map this back to the Green Revolution? The graph of cereal yields shown above from Our World in Data roughly implies that the Green Revolution increased cereal yields in the most affected countries (India, Mexico, Philippines) by 1 ton/hectare within 30 years. So McArthur and McCord’s estimates would imply that it increased national incomes by 30% over that period. This is much lower than Gollin et al’s estimate of 70% over the same period, but it is still substantial. I think this estimate is inflated because of design issues with McArthur and McCord’s study2, but it is still evidence in favor of a positive effect of the GR on incomes.

So I still feel alright concluding that the Green Revolution increased incomes on average, although this is much less certain than Gollin et al make it seem, and could definitely vary across countries like Moscona argues.

Did the Green Revolution make people healthier?

You might be thinking, “Karthik, we know you’re hopelessly tainted by the economic prejudice, and you can only value dollars and cents, but actually the Green Revolution has been disastrous/amazing for human health, and that’s what matters.” So let’s figure out whether either of those things is true.

Once you accept that the Green Revolution increased agricultural yields, it is hard to reject that it increased the amount of calories that people consume and reduced malnourishment. One particularly legible metric of health improvements from more calories is infant mortality. The main paper estimating this impact is von der Goltz et al (2020). They estimate the relationship between HYV adoption and infant mortality across 37 developing countries, using a strategy similar to Gollin et al – they compare subnational regions with different crop mixes to measure different exposure to the Green Revolution. Regions with more rice/wheat/maize were exposed earlier to the GR, while regions with other crops were exposed later, and comparing infant mortality trends between these two types of places tells us the impact of the GR on infant mortality. The results indicate that the GR reduced infant mortality by 2-5 percentage points – a large decrease given the baseline mortality of 18% in the early 1960s. While they can’t pinpoint the source of this infant mortality reduction, it is intuitive to me that pregnant mothers consuming more calories would make their babies less likely to die – and that there would be more calories for the babies themselves. This effect is the most visceral demonstration of the general health benefits of having more calories because of more food production.

But there is also evidence of long-term health harms from the same dietary changes. Singh (2025) estimates the health impacts of the Green Revolution by comparing districts within India. Like Moscona, she compares districts that have high agronomic suitability for rice and wheat HYVs to those with low suitability, before and after 1966 (when HYVs were introduced) to identify the effects of the GR. The important assumption is that without the introduction of HYVs, health outcomes in these high-suitability and low-suitability districts would have evolved in parallel. If this assumption is true, then the difference in how health outcomes evolve can be attributed to the Green Revolution. She shows that high-suitability districts saw a move towards monoculture, producing more rice and wheat at the expense of legumes and millets, which offer more protein and micronutrients. In nutritional terms, calorie production increased by 20%, but entirely from carbs; proteins and micronutrients declined as a share of calories. She shows that people exposed to the Green Revolution during early childhood in high-suitability districts are on average 0.3 cm shorter as adults, have 3 pp higher rates of hypertension and 1.5 pp higher rates of diabetes. So the criticism that the Green Revolution has made people sicker through monoculture is likely to be true.

Unlike the papers about the Green Revolution’s income effects, these papers do not directly disagree, so we don’t have to really dig into their methodology – for what it’s worth, I think both of them are decent, and substantially improve on both Gollin et al and Moscona because they focus on comparing regions within countries.3 This means that the concerns about comparing Africa vs Asia/Latin America don’t apply to these papers.

Comparing these two effects is an unenviable task. On the one hand, fewer infants dying from undernutrition; on the other hand, more chronic disease and stunting. Which of these is more important? There’s no way I can answer that. It might be possible in theory to aggregate the health burden caused by worsening diets and compare it to the benefits of reduced child mortality. But I’m definitely not going to be the person to take on that challenge. So I’m going to acknowledge that the critics have a point, and write this issue off as “the effects on health were mixed.”

Did the Green Revolution preserve the environment?

In reading science papers on the Green Revolution, I was surprised to see that the most commonly debated aspect of it is not whether it reduced poverty or improved nutrition. The most common debate is about the environmental impacts of the Green Revolution.

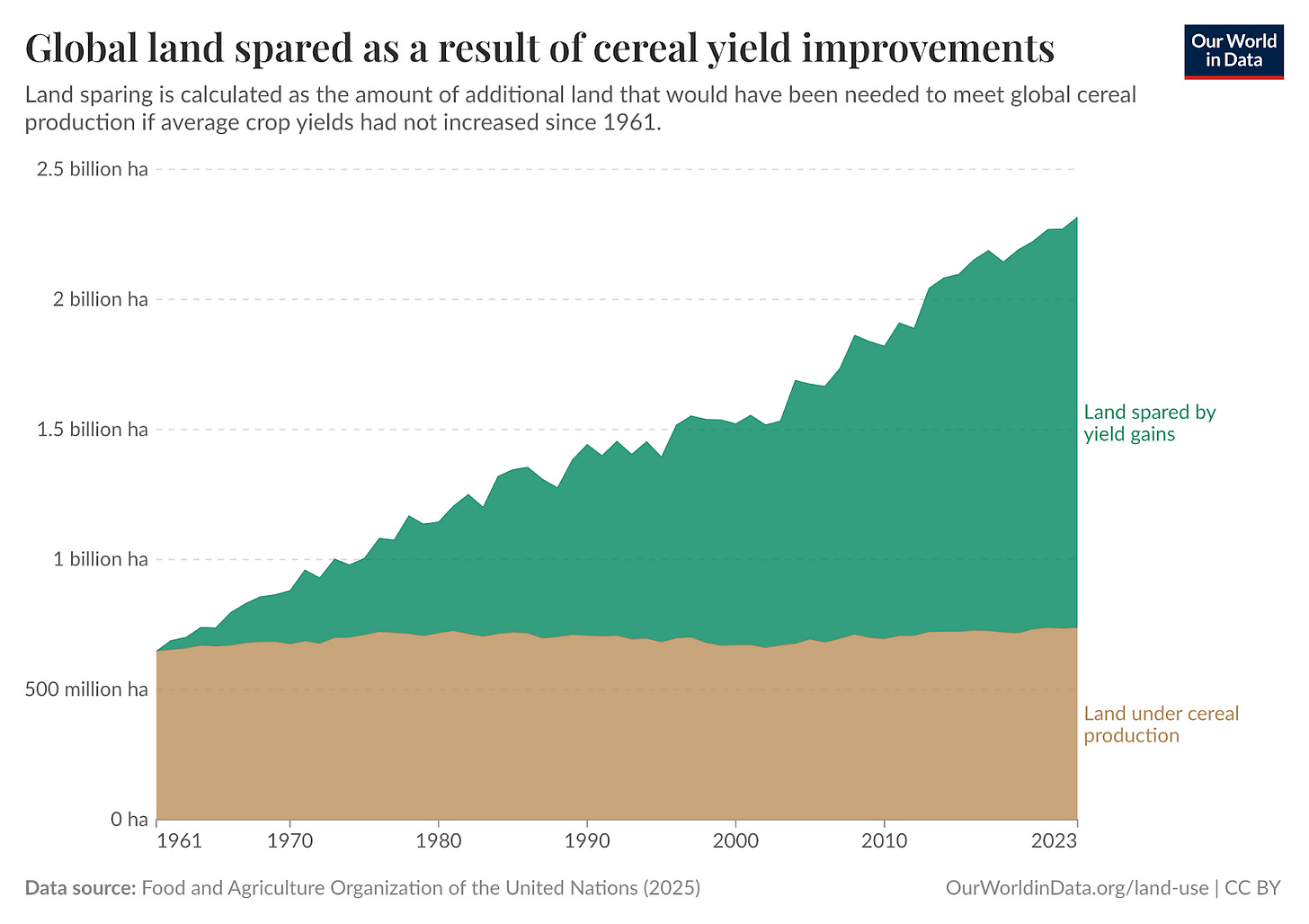

Norman Borlaug, the progenitor of the Green Revolution, argued for his efforts primarily on the basis that they would reduce the amount of land needed to be converted for agricultural use. His logic was that in order to meet world food demand, we could either increase the amount of land used for agriculture, or we could increase yields. By increasing yields, we have spared hundreds of millions of hectares from being placed under cultivation – and the resulting harms from deforesting that land. This land sparing means large amounts of deforestation prevented, less carbon emissions from the farming on that land, and less damage to ecosystems or biodiversity on that land. This idea, now known as the “Borlaug hypothesis”, makes sense to me as a clear environmental benefit of the Green Revolution. This graph from Our World in Data demonstrates how large this effect could be:

The argument of the OWID graph is essentially as follows: we have tripled cereal yields since 1960 while keeping land constant, for a tripling of total cereal output. In order to achieve current world production at 1960 yields, we would have needed to triple the amount of land used for cereals. This would mean adding around 1.5 billion hectares, or 10% of the Earth’s surface area, just for cereals! The environmental impact of that land use would have been devastating (deforestation, groundwater depletion, etc) and thus the Green Revolution spared us from environmental catastrophe.

But that argument is false in its simple form – it assumes that the world food production level we have today is exactly what we would have had without the Green Revolution. There’s no reason that would be true. Food is cheap today, so we consume a lot of it. But without the GR and its yield improvements, food would be expensive, so world food demand would be lower – which means that land use for agriculture would also be lower, since it’s meeting a lower demand. Thus, we need to explicitly model how food supply and demand would be different in a no-GR scenario, to estimate exactly how much land has been spared.

Stevenson et al (2012) do exactly this. They simulate the global economy, imagining how production in agriculture and non-agriculture across the world would respond to a yield reduction. They find that if yields were reduced to the pre-GR level, the total land under cultivation today would increase by 2% – much less than the 300% implied by the OWID graph. The reason is that in order to incentivize land conversion to agriculture in this scenario, food prices have to increase. But if food prices went up, then food demand would fall, so we wouldn’t need as much land to meet that demand. Indeed, part of their simulation result is that world food prices would be 20% higher without the GR. This would reduce world food demand by so much that just a 2% increase in cropland would be enough to meet it. Thus, they argue that the Borlaug hypothesis is generally true, but it is much less significant than you would guess from a simple exercise like the one displayed in the OWID graph.4 Thus, the environmental benefits of the Green Revolution were real but modest.

Stevenson et al is an example of a common type of agricultural economics paper – one that draws its conclusions from a massive simulation model of the world economy, a model with so many parameters and judgment calls that it’s hard to audit the results. I have a hard time evaluating these papers. On the one hand, my economic training places a high premium on papers making only a few important assumptions, and justifying those assumptions clearly, so that anyone can evaluate whether they believe them. On the other hand, reality doesn’t always cleave to simple assumptions, and having the aesthetics of simplicity doesn’t make a story more likely to be true. So I extend some deference to this literature, and I buy that the land-sparing benefits of the GR are small.

While Stevenson et al’s bottom line is generally supportive of the Borlaug hypothesis, not all research I found was supportive. For example, Rudel et al (2009) look at country-level data over time, and they estimate no correlation between increases in yield and decreases in cropland within a country. They conclude that the Borlaug hypothesis doesn’t hold generally. Many papers adopt approaches like this – they look within some country/region and estimate the relationship between yield changes and cropland changes. The problem with this approach is that it only captures decreases in cropland within the country that saw a yield increase. But for thinking about environmental effects, we care about effects on global cropland, not effects on cropland in any particular country. Indeed, the most plausible pathway for the Borlaug hypothesis is that countries seeing yield increases (and thus exporting more food) would allow other countries to reduce their cropland. So this country-level approach is worse at capturing the land-sparing effects of the Green Revolution than the simulation approach of Stevenson et al, and I don’t put much weight on it.

As for potential environmental harms: critics focus on the general features of input-intensive agriculture: that it involves a lot of groundwater usage (leading to depletion and aquifer collapse), and that intensive fertilizer usage damages soil health. These facts are not really contested by supporters of the GR, so the question is simply what we should do with them. I think these issues are subordinate to the land sparing question. If we had to farm more land in the absence of yield increases, we would have to use water regardless; we would have to enrich the soil with some kind of fertilizer regardless. As far as I can tell, it doesn’t matter whether that water/fertilizer is used all in one place, or used across many places. So to the extent that the Green Revolution reduced land usage, it probably also reduced the environmental pressures caused by groundwater usage and fertilizer application.

Conclusion

I came away from this evaluation a lot less enthusiastic than before. Not because it led me to conclude that the Green Revolution was bad! At the end of the day, my bottom line is that the GR increased world food production, it made people richer, it had mixed effects on health, and it had small positive effects on the environment. That’s a pretty solid record, and if I could press a button to duplicate that record with all its harms and benefits, I would.

But that solid record doesn’t live up to the mythology that I had in my head – that I imagine many people have. In my head, the Green Revolution was a victory over nature; I wanted the victory to be total, with no costs on our side. But it seems that the victory was exaggerated and there were some costs. It’s hard not to feel some disorientation at that new picture.

I’m now more sympathetic to the development policymakers who shy away from the “Green Revolution” branding on agricultural policy. I can see that the label promises too much, and comes with too much baggage. We want the Green Revolution to be a heroic tale, but it’s only great policy.

Technically speaking, this is a “weak instrument” concern – if potential yield improvements from HYVs only weakly track actual yield improvements from HYVs, then Moscona’s strategy will give us unreliable estimates of the impact of actual yield improvements on country incomes. Indeed, Moscona’s first-stage regression shows a pretty low F-statistic of 9, meaning that the subsequent analysis is difficult to trust.

Specifically, I’m concerned that countries geographically positioned to access fertilizer are also better positioned to trade with the world across a variety of sectors. If that trade helps with the growth process in ways that are not related to agriculture, then McArthur and McCord would still attribute those effects to agricultural yield growth, which would be an overestimate.

It’s worth noting that Moscona also does a subnational analysis, comparing income in districts across India to see whether more GR-exposed districts see higher income growth. But I don’t foreground this exercise because if agricultural produce is traded across districts, then the difference between more- and less-exposed districts is not actually the impact of the GR, since both groups could benefit from the agricultural trade induced by yield growth.

They actually argue that the environmental harm averted is even smaller than this 2% would imply, because they estimate that only 10% of this added cropland would have come from previously-forested land, and that most of it would come from pastures (which is less environmentally harmful to convert into cropland). This is based on some particularly difficult-to-audit assumptions about the relative propensity to convert forests vs pastures, and it seems implausibly low, so I don’t highlight this argument in the main text.

Woah, 18% infant mortality in 1960s??? We have come such a long way

Good point about how food would be expensive without the Green Revolution, so there would be much less land used for agriculture. I hadn't thought of this before. I suppose this implies that without the Green Revolution, global meat consumption would be a lot lower too - since growing animals for food is a particularly inefficient and costly use of agricultural land.

So that's a strike against the Green Revolution - it has likely enabled more factory farming and the accompanying animal cruelty.