When rising wages are a bad omen

Obsolescence rents from AI automation risk

Anthropic recently posted a job for a writer that paid an eye-popping $300,000 a year. A lot of discourse around this job involved writers taking a victory lap, offering it as evidence that AI will not replace writing, that good writing will become even more valuable in the future. This was a specific case of a general tendency: people often forecast an occupation’s robustness using trends in wages.

But this is a mistake. Jobs facing future obsolescence tend to see wage increases, not decreases. This counterintuitive fact comes from a concept known as obsolescence rents.

Obsolescence rents

Career choice is a long-term investment. When you decide to become a lawyer or a programmer or a truck driver, you consider not just the money you’ll make in your first year, but the money you’ll make in twenty years. That includes considering whether that job will even exist in twenty years.

So imagine you’re a young worker choosing a career, and technology threatens one particular job in the future. But notably, technology cannot yet replace workers at that job, so you can still get a job in that sector if you want to. Do you take that job?

Maybe! But the risk of future job loss reduces your willingness to work in that profession. You need to be compensated for the risk that you will be stuck with obsolete skills halfway through your career, and forced to go through the unpleasantness and uncertainty of re-skilling for a new job. (You might protest that young people don’t have infinite foresight to see the future – but even if some fraction of them are attentive to the risk of future job loss, the argument below makes sense.)

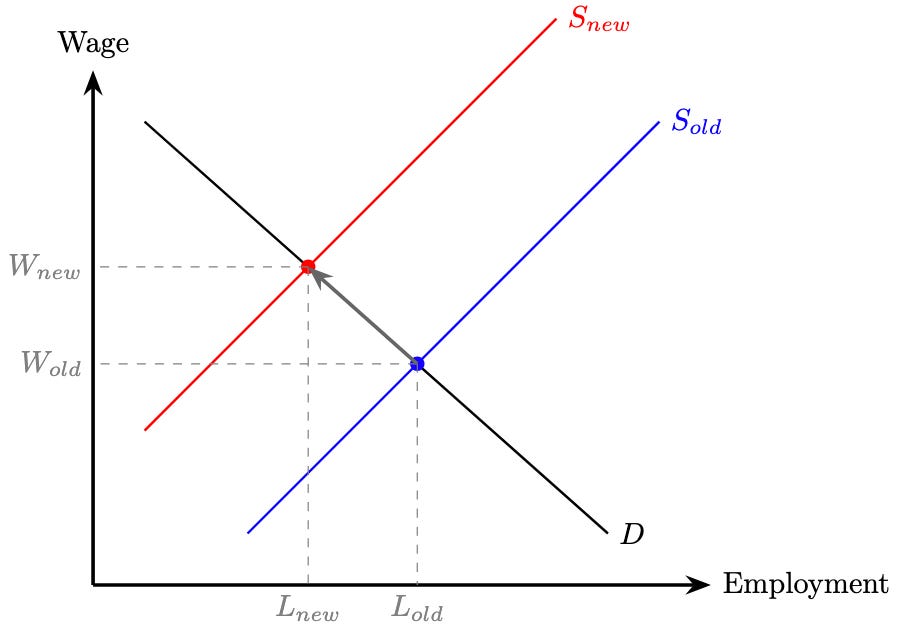

This risk of future job loss shows up as a leftward shift in the labor supply curve – at any particular wage, workers are less willing to work in the job than they were before:

This shift in the supply curve has two immediate predictions that you can see in the graph.

Employment falls (L_new < L_old). Because the risk of obsolescence makes workers find a job unattractive, fewer people take that job now.

Wages rise (W_new > W_old). Since the job is not yet obsolete, employers still need to find workers to do it. But to compensate for the risk of obsolescence, they need to pay higher wages to hire those necessary workers.

Thus, the counterintuitive conclusion: impending obsolescence makes wages rise.

We can make one final observation. The threat of obsolescence also affects who chooses to work in a job. A 25-year-old has forty years of working life ahead of them; a 55-year-old has ten. The 55-year-old may retire before obsolescence occurs, but the 25-year-old has no such luxury. Thus, young workers are disproportionately filtered out of an occupation by the threat of obsolescence. This leads to a third prediction:

The profession becomes older in age composition. Younger workers are less likely to enter the profession and more likely to leave it than older workers.

So this is the theory: impending obsolescence leads to falling employment, rising wages, and aging workforce composition. Does it happen in reality?

Case study: motor trucks

The transition from horse-drawn freight to motor trucks in early 20th century America provides the clearest historical evidence for obsolescence rents. A recent economic study uses this transition to test all three predictions of the obsolescence rents story.

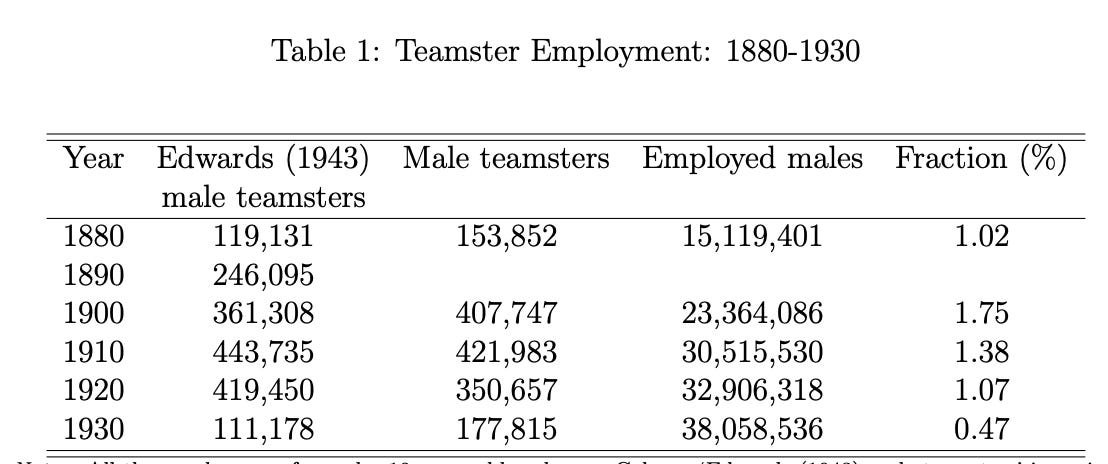

Before trucks, freight was carried on wagons pulled by teams of horses. The workers who drove these wagons were called teamsters – literally, people who managed teams of horses. In 1900, there were over 400,000 teamsters in the United States.

Yet motor trucks were anticipated for a long time. In 1895, Thomas Edison declared that it was “only a question of time when the carriages and trucks in every larger city will be run with motors.” The first commercial motor truck was sold in 1897. The technology was real. At the same time, trucks remained firmly on the horizon. Their design was still uncertain; competing designs used steam, electricity, or gasoline, and nobody knew which design would win. More importantly, road infrastructure wasn’t good enough for trucks in the early days. They were expensive, broke down frequently, and couldn’t travel far outside major cities.

World War I pulled trucks forward from the future, as American manufacturers built thousands of standardized military trucks for use in the war. After the war ended in 1918, all of that production capacity turned to the civilian market, and surplus military trucks flooded into civilian use.

You can track the growing anticipation in the pages of Scientific American, which served as a contemporary forum for discussing the cutting edge of technology. Between 1900 and 1910, only eleven articles mentioned motor trucks, and almost none forecast trucks replacing teamsters. But between 1910 and 1920, ninety-six articles discussed trucks.1 A 1909 article cautiously suggested trucks might be superior to horses in New York City – but warned that “two weeks at the factory is not sufficient to change a stable hand into a competent driver.” By 1918, the tone had shifted completely: “Prior to the war, the motor truck was making steady progress towards ultimate complete employment... But the war accelerated its adoption, perhaps by twenty years.” By 1930, the transition was largely complete. Motor trucks had taken over urban freight hauling.

The researchers use the historical transition from teamsters to motor trucks to test the three predictions of obsolescence rents: falling employment, rising wages, and aging workforce.

First, did teamsters see falling employment before trucks were actually deployed? Yes. The researchers used Census data to track how many people worked as teamsters in 1900, 1910, 1920, and 1930. Teamster employment rose from 1900 to 1910, when motor trucks were still a distant prospect. But it fell slightly from 1910 to 1920, even though trucks weren’t yet widespread. This is the sign of obsolescence rents: teamster employment dropped before trucks were actually deployed. Of course, employment absolutely cratered between 1920 and 1930 as trucks took to the road, but that is the part that we expected already.

Could other factors explain the 1910-1920 decline? Of course. WWI pulled workers into many occupations whose demand spiked during the war effort, and perhaps some of them stuck with those occupations after the war. But the timing of the decline is consistent with workers avoiding a profession they expected to disappear.

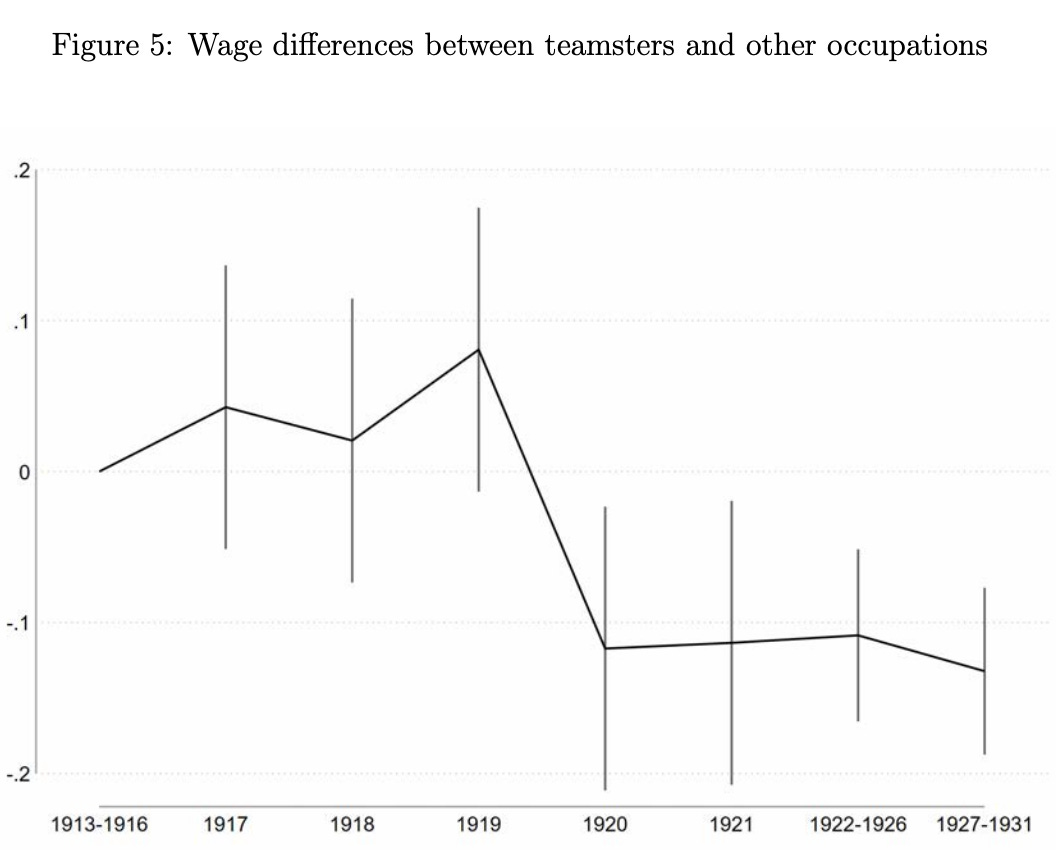

Second, did teamsters actually see rising wages before trucks were deployed? This is the important one, since it gives the most direct evidence about whether we should actually see rising wages as a bad omen. The researchers compared the wages of teamsters to wages in “close trades” – that is, professions that required similar skills and earned similar wages before trucks appeared (e.g. carpenters, building laborers, painters).

During the peak of anticipation, wages for teamsters did seem to rise relative to close trades, before cratering in 1920 as trucks hit the road. This isn’t slam dunk evidence by any means – the wage increase during the anticipatory period isn’t statistically significant – but it points in the right direction.

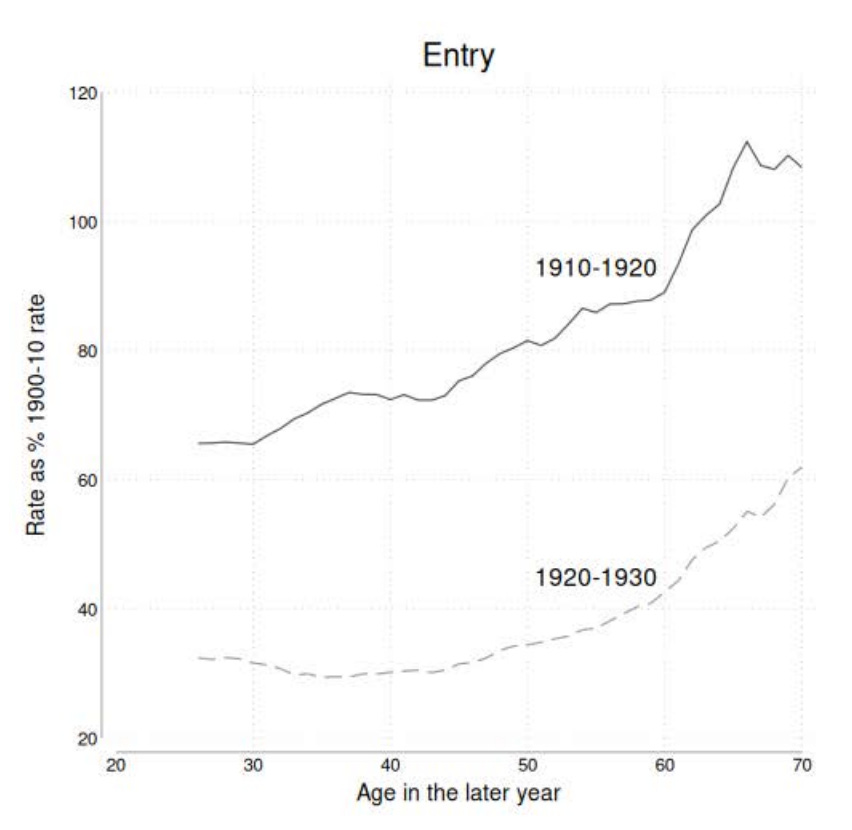

Third, did the age composition of teamsters become older? In a way this is the most convincing evidence for obsolescence rents, because it is the most specific. Wages and employment can fluctuate for all kinds of reasons not captured by the simple story we are telling. But “a profession that was historically full of young people suddenly becomes full of older people” is a much more tailored prediction.

Between 1910 and 1920,2 young workers’ entry into teamster employment dropped by 30% compared to the previous decade. But older workers’ entry actually increased by 20%.3 The pattern grew more pronounced after trucks were deployed en masse. Between 1920 and 1930, all age groups became much less likely to become teamsters – but old workers saw a decline of 40%, much less than the 60-70% decline for young workers. Despite being physically demanding work that should favor the young, being a teamster became an old man’s job as trucks arrived on the horizon.

Will AI produce obsolescence rents?

The arrival of motor trucks in the 1910s parallels the state of AI today:

Both are technologies which definitely exist, and are widely known to have the potential to automate jobs in the future.

However, neither can automate jobs today due to limitations of the current technology and the absence of complementary infrastructure (trucks needed roads and repair mechanics, AI needs organizational changes/regulatory freedom).

When this automation will occur is a question with huge uncertainty.

These three conditions are exactly the conditions under which we expect obsolescence rents to appear. Jobs like writing or translation are still needed today, but people can see the writing on the wall for them. So in order to attract people to fill the jobs that are still needed today requires higher wages. Perhaps Anthropic is posting a high wage for a writer because excellent writers need to be persuaded to continue working as writers rather than accumulating more future-proof career capital.4

The important takeaway is that if you want to forecast automation risk:

Do not use wages as a signal of occupational health, at least not if you’re interpreting wage increases as a positive signal.

Do use employment/job postings as a signal of occupational health. “Translator wages are up, so AI won’t automate translators” is a bad argument. “Translator employment is up, so AI is more likely to augment than automate translators” is a better argument.

Do use age composition as a signal of occupational health. If young workers are reluctant to take a job, it is a good sign that at least they believe it will be automated in the future (though who knows if they’re right!)

Caveats

There are a few limitations to this argument. First, obsolescence rents are obviously not the only reason for wages to go up, and it is clearly not the case that wages going up is always a bad sign. For example, wages for software engineers exploded in the 2000s because software became a growing part of the economy, not because software engineers were at risk of obsolescence (then). So my point is not that rising wages are always a bad sign, just that it’s important to distinguish between “wages went up because the sector’s demand for workers is healthy and growing” and “wages went up because willingness to work in this sector is anemic and falling”. Both scenarios would lead to wage increases, so wage increases alone cannot distinguish between these scenarios.

Second, these predictions rely on workers actually factoring the chances of future obsolescence into their career choice. If nobody believes that their job will become obsolete, then there will be no shift in willingness to work in a job, and no rising wages/falling employment/aging of the profession. If you believe that people are asleep at the wheel and not considering the risk of their job being automated, then this argument has no insight for you. But I don’t think people are asleep at the wheel. Many people remain skeptical that AI will replace their jobs, but this skepticism has declined sharply since 2022. People’s guesses about the future may lag behind the best available information out there, but they are clearly responsive to the growth of AI. The market for “what should I do to future-proof my career” advice is enormous. Even if people are only partially responsive to automation risk, we should expect to see obsolescence rents.

Third, it is a key assumption that the new technology’s impact is automation. If AI is actually going to augment workers (making them more productive), then the predictions are exactly flipped from what I’ve described. Suddenly, instead of expecting a reduced future income, workers expect an increase in their future income from entering that job. The resulting influx of young workers would increase employment, bid down wages, and make the profession younger. Once again, we are in backwards-land, where falling wages are a good omen. In this case, we should still read occupational health from employment and demographics, rather than from wages.

One particularly amusing quote from these articles that the researchers highlight is from an article from 1915, arguing for a “mixed system of horses and motors” to replace horses instead of exclusively using motors. Ah, yes, truly equal contributions going on there. It seems that the 2024-era refrain of “AI won’t take your job, but a person using AI will” is part of a long tradition.

The phrasing “from 1910 to 1920” makes it sound like these results could be an artifact of young workers being diverted into military service and away from being teamsters – but in fact the employment is measured in 1920, after the war, so that is not a concern.

This is a more complex exercise than just looking at how the average age of teamsters changed, which might be your first instinct. But it’s necessary – if teamster employment fell uniformly, and the remaining teamsters got older, then the average age would go up mechanically without any relationship to obsolescence rents. Thus, the need to compare entry rates to the past within each age group.

Of course, this particular example is hugely confounded by the fact that working at Anthropic is direct insurance against being unemployed AI progress, so think of this as an illustrative example rather than an actual explanation for why Anthropic offers a high salary.