What happened to technology transfer?

The death of the 20th century's greatest development policy

Minutiae: I’ve started a second Substack with an “after dark” flavor, where I plan to write fiction, literary criticism, and other fragments that don’t match the theme of this vaunted publication. I plan to post (here or there) every day in November.

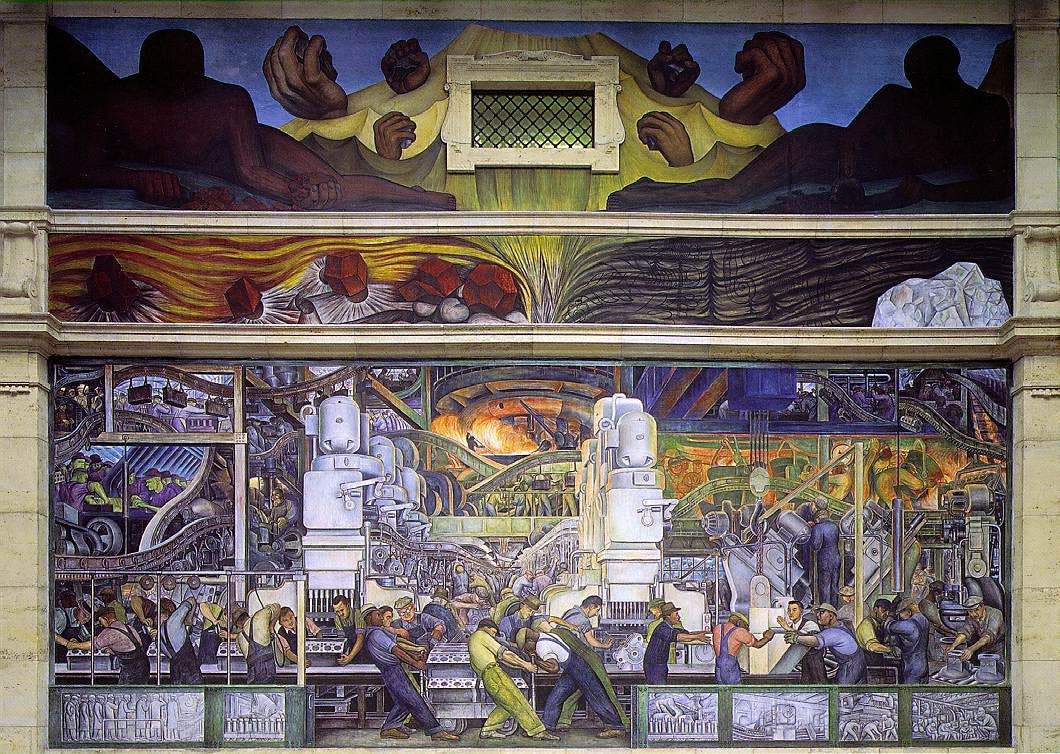

The economic growth stories of the past century were defined by technology transfer. The entire reconstruction of Europe as a set of advanced economies happened through the Marshall Plan, the large-scale transfer of knowledge and infrastructure from the US to European countries. Japan, Taiwan, China, and Korea all grew their industries using technology imported from the US, US, Soviet Union, and Japan respectively. In all of these countries, the growth of advanced industries was catalyzed by receiving that technology from another country – through a combination of supplying special equipment, and training workers to work in those industries.

But despite the power of this kind of technology transfer, these agreements don’t happen anymore. Today, policies around foreign investment in developing countries are framed in terms of creating jobs or gaining tax revenue – not in terms of gaining technological capabilities. It often comes with no strings attached, and no intended technological benefit for the host country at all.

So what happened to technology transfer agreements?

Technology transfer helps industrial growth

The most comprehensive technology transfer effort in history happened as part of the Marshall Plan, with the US aiming to bring technology and productive capacity back to European firms after they were devastated during World War II. The US sponsored training trips for managers from European firms to visit American factories, and they provided subsidized loans to buy advanced equipment from American firms, bringing the European firms back to the technological frontier. Giorcelli (2019) evaluates this program’s impact on Italian firms. She compares firms that received the training and subsidized machines with firms that could not receive them due to budget cuts on the American side – reasoning that without the budget cut, these firms are otherwise identical, so comparing their trajectories gives us the effect of the Marshall Plan’s productivity program. She finds that 15 years after the Italian firms received the training and equipment, they were 90% more productive and had 20% higher profits than their counterparts who missed out on the program due to budget cuts. These results make it pretty likely that the Marshall Plan’s technology transfer program helped stimulate industrial growth in Europe.

Uncannily similar evidence comes from the other side of the Iron Curtain. In the 1950s, the Soviet Union supported the development of large heavy-industrial clusters in China as part of their alliance. They exported state-of-the-art equipment to set up Chinese plants, and trained Chinese technicians in how to operate and maintain these plants. Giorcelli and Li (2025) evaluate this program using a natural experiment – many of the proposed transfers were cancelled abruptly as part of the Sino-Soviet split, while others were completed before this split. They find that the projects which received Soviet training and machines became more productive than the plants that were supposed to receive Soviet transfers, but didn’t. Strikingly, this benefit extended beyond Soviet knowhow and into helping the plants do their own internal R&D. For example, Soviet steel furnaces were made obsolete in the 1960s by new continuous-casting furnaces; yet the Chinese plants that received Soviet transfers actually became more likely to adopt continuous-casting furnaces, showing that they weren’t just blindly using imported machines but were actually keeping up with frontier capabilities. Decades after the initial transfer, these plants produced 50% more and exported 30% more than the plants that didn’t receive Soviet transfers. Much of China’s vaunted industrial capacity was built during this era, and thus can be attributed to Soviet technology transfer.

But this isn’t an essay about how technology transfer is good. That essay would fall flat, because technology transfer is off the menu today. Today, developing countries court multinational investment, rather than imposing conditions on it.

So given the unreasonable effectiveness of technology transfer, why doesn’t it happen anymore?

Why technology transfer happened to begin with

Technology transfer is a strange idea when you think about it. After all, companies invested tremendous effort and resources in reaching their level of technological capability. Why would they want to sell those capabilities to another firm? Even if they were paid handsomely for it, they would just be seeding their own end – creating firms that would eventually be able to outcompete them. It’s hard to imagine a contract that makes this risk worthwhile for them. So the puzzle is not why technology transfer doesn’t happen now – the puzzle is why technology transfer ever happened to begin with.

There were three main reasons why technology transfer was so common in the post-war era:

Geopolitical alignment. What all the most successful case studies of technology transfer have in common is that they were between geopolitically aligned countries. In the examples studied above, the US wanted to prop up Europe as part of the Marshall Plan, while the Soviet Union wanted to bolster another communist power. These motivations meant that the technology-exporting companies did not have to benefit very much – the respective governments were invested enough to encourage their companies to transfer technology to the recipient countries. It is hard to imagine companies protesting too much when they have been ordered to transfer technology in order to fight the enemy.

Market access. It’s hard to picture this now in the era of globalization, but it used to be quite difficult for Western firms to access other countries. They wanted access to other countries in two ways – as destinations in which to sell their products, and as origins in which to outsource their manufacturing. Both of these forms of access were hard to come by. Exporting to developing countries was held back by “import substitution industrialization” – the policy framework adopted by many developing countries, in which they reduced imports in order to force domestic firms to produce in essential sectors. Investing in setting up factories was often similarly restricted – for example, in India, foreign ownership in companies was capped at 40%, making it impossible for a foreign company to set up and majority-own their factory. Faced with these barriers, companies were much more willing to consider demands such as “you need to license your technology to a domestic firm in order to sell goods/set up a factory in our country”.

Creating a suitable supplier. If companies want to outsource production of goods with any technological sophistication, they can have a hard time finding a suitable supplier – one that is cheap enough to be worth outsourcing to, but is also high-quality enough to produce according to standards. Technology transfer is a way for companies to create that suitable supplier when one might not exist. For example, Bangladesh’s textile industry was built up by technology transfer from Korean textile firms, who wanted to produce in Bangladesh to have easier export access to the US.

These three forces conspired to create the landscape of successful technology transfer agreements that characterized the mid-20th century.

Today’s landscape

Of the three motivations for firms to transfer technology to developing countries, do any of them still apply?

Geopolitical alignment kind of applies today. The “China plus one” approach to supply chains involves firms preferring to not rely on Chinese suppliers because of geopolitical risk. India has certainly been appealing to countries on this basis. But by and large, firms don’t consider licensing technology on the basis of geopolitics anymore.

Market access doesn’t apply today. The world is far too globalized for it to be a valuable carrot. There are too many countries with big markets who don’t demand technology transfer. There are still a small number of countries with large enough markets to make such demands – China, India and Brazil come to mind. But only China is actually willing to make those demands.

Getting a cheaper supplier does still apply somewhat. But today, international firms would rather simply invest directly in setting up factories within countries where it’s cheap to produce. That way, they can reduce their production costs, without the baggage of licensing and transferring technology to local firms.

Overall, the motivations for companies to license out their technology to firms in developing countries are weaker than ever before.

Another significant barrier is that the global policy environment has become quite hostile to technology transfer as an enforced requirement on foreign companies. As part of the Washington Consensus, developing countries came under pressure to liberalize their economies – i.e. attract foreign investment by offering hospitable conditions, not by imposing conditions on investors. Most post-1990 investment treaties between countries explicitly prohibit governments from requiring technology transfer as investment conditions. So if a country tried to mandate technology licensing as part of foreign investment, it could be violating an international agreement. This legal status has a chilling effect: governments know that overt technology transfer conditions could invite trade disputes or investor-state arbitration lawsuits, so they functionally cannot do so.

Two arrangements have replaced technology transfer today. The first is foreign direct investment. FDI involves foreign companies directly investing in and operating a factory in the host country, rather than operating through a local partner. For example, a car manufacturer like Toyota might operate a plant in Pakistan directly, rather than outsourcing to a local partner as they might have in the past. This approach is the default approach to outsourcing in sectors where the manufacturing process is technologically complex and can’t be

The other arrangement that replaces technology transfer is simply having international supply chains. Rather than setting up a factory in a developing country to produce that input, a multinational firm can simply buy cheaper inputs from suppliers in that country. This arrangement is especially feasible when the input being supplied is not very technologically sophisticated, so that the supplier doesn’t need special training and equipment to supply it.

Between these two forms of investment, international firms can achieve their market access and supplier goals without the need for technology transfer – and with legal protection from countries that might push them to engage in technology transfer.

China is the only country that still pushes hard on getting technology transfer, through their controversial quid pro quo policy – that in order for multinationals to access the Chinese market, they need to transfer their technology to a Chinese partner firm, through a joint venture. China’s market is large enough that firms are actually willing to agree to these conditions. It’s no wonder that researchers estimate that this policy has helped China, while harming its FDI partners. But most countries don’t have the will or market size to enforce a quid pro quo policy, which is why technology transfer agreements have all but vanished.

Can foreign investment and supply chains achieve the same outcomes?

Can developing countries benefit from FDI and supply chains in the same way that they benefited from technology transfer?

Maybe. There is a large literature on the effects of FDI on developing countries, most of which estimates that it has positive effects. But these studies are not generally high-quality – they’re only slightly more careful than simple correlation. The challenge is that we don’t want to evaluate FDI against the standard of being better than no-FDI; we want to evaluate it against technology transfer. And while FDI certainly bleeds knowledge – domestic firms learn from being in proximity to foreign firms – it doesn’t do so nearly as efficiently as directly learning from those firms as part of technology transfer.

Supply chains present their own learning opportunities, because international firms have an incentive to share knowledge with their suppliers to make them more efficient, even in the absence of a technology transfer agreement. Alfaro-Urena et al (2022) show this effect in Costa Rica. They compare Costa Rican firms that sell to multinationals with comparable firms that don’t sell to multinationals, showing that the former group see larger growth in productivity and sales (including to non-multinational buyers) after the multinational enters. This is a microcosm of how participating in global value chains can upgrade domestic firms, by giving them buyers who will hold them to high-quality standards, and give them the training necessary to achieve those standards.

So while we are unlikely to recreate the power of mid-20th century technology transfer agreements, the main benefit to the recipient countries – having domestic firms learn from more advanced foreign firms – may still be achievable through FDI and supply chain linkages.

Conclusion

Technology transfer agreements powered the most successful industrialization stories of the 20th century. But they required conditions that no longer exist: geopolitical alliances willing to subsidize transfers, closed markets that gave developing countries leverage, and production networks fragmented enough that firms needed to create capable local partners. Globalization eliminated these conditions. Today, firms can access markets and production capacity without transferring technology, and international trade law makes it illegal for countries to enforce technology transfer requirements.

China’s continued use of technology transfer requirements shows that technology transfer still works to grow domestic industries, but it also reveals why other countries can’t copy that approach, without the market size and leverage that China has.

FDI and supply chains are likely not as transformative as technology transfer was, because they involve more muted transfers of knowledge. But they are still likely to be the best option on the table today.